I run courses on Maharishi AyurVeda, food and cooking and one frequently asked question is, “What’s the best oil to cook with?”. I respond that my favourite cooking oils are ghee, coconut oil and olive oil*, in that order.

There is no controversy surrounding olive oil – after all, haven’t there been lots of TV ads implying that perpetual youth and vitality are almost guaranteed through consuming it? But, ghee and coconut oil are saturated fats, and surely saturated fats are evil and sources of high cholesterol and heart disease?

All oils contain a mixture of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids and our body needs a steady supply of each. Animal fats such as lard, ghee and butter, contain a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids, as does coconut oil. The conventional wisdom has been that a high consumption of saturated fat leads to a host of negative outcomes, such as high cholesterol, heart disease, obesity and Alzheimer’s disease.

Although for hundreds of thousands of years the human diet has been rich in animal-sourced fats, heart disease seems to be very much a modern phenomenon. Why then are saturated fats so demonised?

Dr Malcolm Kendrick

Flawed research on saturated fats

One must-read book I highly recommend is The Great Cholesterol Con by Dr Malcom Kendrick. In it, Dr Kendrick shows that the highly influential Seven Countries Study, conducted in 1958 by Ancel Keys, which established the link between the consumption of saturated fats and heart disease, was deeply flawed.

Keys’ team looked at the saturated fat consumption of people in seven countries (Italy, Greece, former Yugoslavia, Netherlands, Finland, USA and Japan) and found a direct link between heart disease, cholesterol and saturated fat.

Yet, as Dr Kendrick points out, if Ancel Keys had chosen the following seven countries instead – Finland, Israel, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France and Sweden – the results would have demonstrated the exact opposite outcome.

Keys originally gathered data from 22 countries but selectively chose only those where the figures suited his prior hypothesis – that there was a link between saturated fat consumption and heart disease. He conveniently omitted:

- Countries where people consumed large amounts of saturated fat, but where heart disease was low, such as Norway and Holland

- Countries such as Chile, where there is low fat consumption yet high heart disease rates.

In subsequent years, Ancel Keys gave up on the idea that diet can affect our cholesterol levels. Yet the myth perpetuates and that may have more to do with the financial interests within the food industry than good science.

Saturated fats equated with good health

Studies of tribes in Africa have shown that the intake of large quantities of animal fat seems to result in very low blood cholesterol. For example, the Samburu people drink almost two gallons of raw milk and eat about a pound of meat and each day. Milk from their Zebu cattle has a far higher fat content than milk from European cows. This means that the average Samburu consumes over twice the animal fat of the average European or American, yet their cholesterol is much lower.2 Apologists for the saturated fats = high cholesterol = heart disease hypothesis argue that this tribe may have a genetic pre-disposition that is protective against heart disease, but no evidence for this has been ever been presented.

Also, Pacific Islanders, who obtain 30% to 60% of their total calorie intake from saturated coconut oil, have extremely low rates of cardiovascular disease.3

In Japan there has been a continuous decline in mortality from coronary heart disease, despite a marked and continuous rise in total cholesterol levels (since Ancel Keys’s study in the 50s) – not at all what those who have bought into the ‘bad fats’/cholesterol/heart disease theory would expect.

Toward the later part of his book, Dr Malcom Kendrick concludes that, although there is virtually no link between saturated fats and the rapid rise of heart disease throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, there is a clear link between individual and sociological stress levels and heart disease.

Now we’ve assured ourselves that it’s probably okay to include a bit of ghee and coconut oil in our cooking, why favour these over safer sounding vegetable oils?

Why cook with saturated fats?

Why cook with saturated fats?

Certain vegetable oils, such as sunflower oil and corn oil – among the most commonly found oils on our supermarket shelves – become toxic and potentially cancer-creating when heated. Both corn and sunflower oil are rich in polyunsaturated fats, and we do need a certain amount of these type of fats in our diet. Yet the molecular structure of polyunsaturated fats is inherently unstable and when heated, such oils become oxidised and high concentration of chemicals such as aldehydes and acrolein are produced. The oxidation process creates free radicals that can damage DNA, as can acrolein. High levels of aldehydes in foods are associated with cancer, heart disease and dementia.

Saturated fats are far more stable in their molecular structure, which is why butter, ghee, lard and coconut oil solidify at room temperature. These fats don’t tend to oxidise when heated and very low levels of damaging chemicals, such as aldehydes, are created during cooking.

Balancing omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids

Balancing omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids

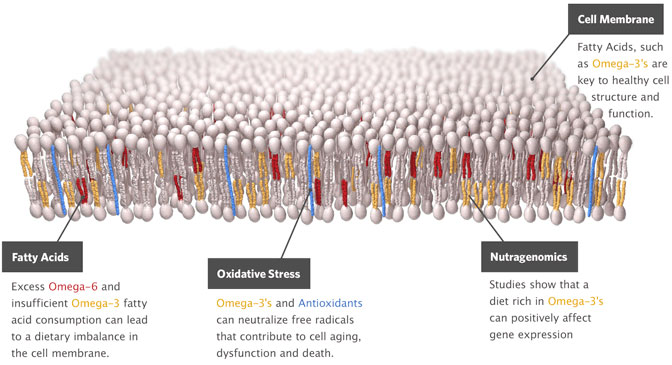

Omega-6 and omega-3 are essential fatty acids that are necessary for human health and that play a crucial role in the functioning of our brain, as well as in our general growth and development. Yet our body cannot create them – they must be obtained from food.

Some say that our brain, and the rest of our body, needs at least a 4:1 ratio of omega 6 fatty acids to omega 3 (some even claim that ideally the ratio should be 1:1). In Western diets the ratio is usually between 15:1 and 17:1.4

Although we need omega-6, a too-high proportion of this fatty acid in our diet has an inflammatory effect and promotes a number of diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Oxford University emeritus professor of neuroscience, Professor John Stein, claims that partly because of the increased use of omega-6-rich corn and sunflower oils in food processing, and in cooking, “the human brain is changing in a way that is as serious as climate change threatens to be”.

“If you eat too much corn oil or sunflower oil, the brain is absorbing too much omega-6, and that effectively forces out omega-3,” said Professor Stein. “I believe the lack of omega-3 is a powerful contributory factor to such problems as increasing mental health issues and other problems such as dyslexia.”

Butter, ghee, coconut oil, lard, palm oil and olive oil are all relatively low in omega-6 and are higher in omega-3 than the cooking oils usually found in supermarkets. These fats have also been used in various cooking traditions for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Grass-fed, pasture-raised

Grass-fed, pasture-raised

When it comes to animal fats such as lard, butter and ghee, make sure that the animals they are derived from are grass-fed, live most of the year out of doors, and are part of an organic system. Grass and other herbs found in fields are the natural foods for cows and this diet will help ensure that the fat they produce has a health ratio of omega-6 to omega-3.

Most cows start their lives grazing in fields. In conventional systems, cows intended for meat consumption, spend their last 2-12 months in crowded feedlots, being fattened on grains and soya ready for slaughter (in Europe massive quantities of genetically modified maize and soya are imported for animal feed). In the US, regular doses of antibiotics and growth hormones (a combination of natural and synthetic anabolic steroids) are used to further speed up the fattening process. In Europe such growth hormones are disallowed, as is the use of antibiotics as growth promoters to help fatten livestock. However, antibiotics are still routinely fed to livestock kept in intensive conditions as a supposed disease preventative.

Another US-led trend that we are increasingly seeing in Europe, is the use of feedlots for dairy production. Because of the ridiculously low milk prices imposed by supermarkets, dairy farmers are gradually being forced down the feedlot route. Grain (instead of grass), artificial insemination, milking regimens, feed additives and antibiotics are used to force cows to produce more milk than ever – it’s estimated that cows today produce over four times as much milk as in the 1950s. The natural life expectancy of a cow should be around 20 years. Modern conventional dairy farming practices create so much wear and tear and illness within cows, that they are now usually slaughtered after only 5 years as milk production declines after that age.

In the USA, even if a cow has spent almost all its life in a feedlot, as long as they have spent a certain amount of time eating grass (often just in the form of hay), supermarkets are allowed to use the terms ‘grass-fed’. Fortunately, the term ‘grass-fed’ seems to have a bit more meaning in Europe.

Organic is best

Organic is best

I always go for organic everything, including the animal fats and vegetable oils I use. One reason is selfish – I don’t want to contaminate my body with agrochemical residues and I want the highest quality nutrition. The other reason is that I would like to know that the animals which supply my butter and ghee have had the best possible life.

I don’t mind spending a little more on organic food. The proportion of income that we spend on food is said to be the lowest it has ever been in history. Why not pay just a little more to give yourself better quality nutrition, to help improve your ecosystem and to improve the lives of farm animals?

References

- Nina Teicholz. (2014) “The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet” Simon & Shuster New York

- Shaper AG. Cardiovascular studies in the Samburu tribe of northern Kenya. American Heart Journal 1962;63:437-442

- Kaunitz H, Dayrit CS. Coconut oil consumption and coronary heart disease. Philippine Journal of Internal Medicine, 1992;30:165-171

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12442909

* As it contains mostly monounsaturated oils, which are more molecular stability than polyunsaturates, oilive oil can cope with some degree of heat before its structure starts breaking up and causing problems. Even so, when I’m cooking I do not use olive oil for anything more than a light vegetable sauté.